After World War II, thousands of European immigrants came to Canada in the 1950s. They changed this country for the better– enriching it with different cultures, different traditions, and fascinating new artistic directions.

Angelo Tedesco (a former Venetian glass blower, master glass cutter and engraver) following many of his countrymen from Murano, Italy - settled in Montreal in 1952. He sponsored his brother, Luigi Tedesco, and his brother-in-law, Sergio Pagnin and their families to Canada. Both men were master glass blowers having apprenticed under Venetian Maestri, and in addition to his unique skillset, Sergio was also a chemist. In 1958, the three, with a French-Canadian partner, established a small (1 furnace) glassmaking factory “Les Industries de Verre et Miroirs” on Saint Laurent Boulevard. The budget was tight; requiring the artisans to build their own crucibles, warming ovens and benches. On July 9th, the name was changed to Murano Glass. Although Murano Glass was Eastern Canada’s first art glass factory (Altaglass was established in 1950 and moved to making decorative glass in 1952 in Alberta), the Montreal area became a beacon for other glassblowers, and it was not long before Murano Glass was only one of several small Italian/Canadian glass factories in Quebec.

Across the border in Ontario, the city of Cornwall was facing massive job losses which resulted from the completion of the St. Lawrence Seaway and the closure of the Dundas, Canada and Glengarry cotton mills. Unemployment in the city of 43,000 was at ten per cent and it seemed the economic devastation the city was suffering would likely worsen. To fight the oncoming recession and to attract new industry, the city’s industrial commissioner and a dozen local businessmen created the Cornwall Industrial Development Limited (CIDL). The federal government also designated Cornwall “depressed” and thereby eligible for tax incentives that could be offered to attract new business.

Murano Glass was one of the 18 businesses that relocated to Cornwall; the company having suffered a devastation of their own in the form of a destructive fire after only a few months of operation. The industrial relocation, tax incentives in addition to the prospect of a location in the renovated waterfront Cotton Mills Development offered by CIDL was too good to pass up. The business relocated to Ontario and production resumed in September of 1962.

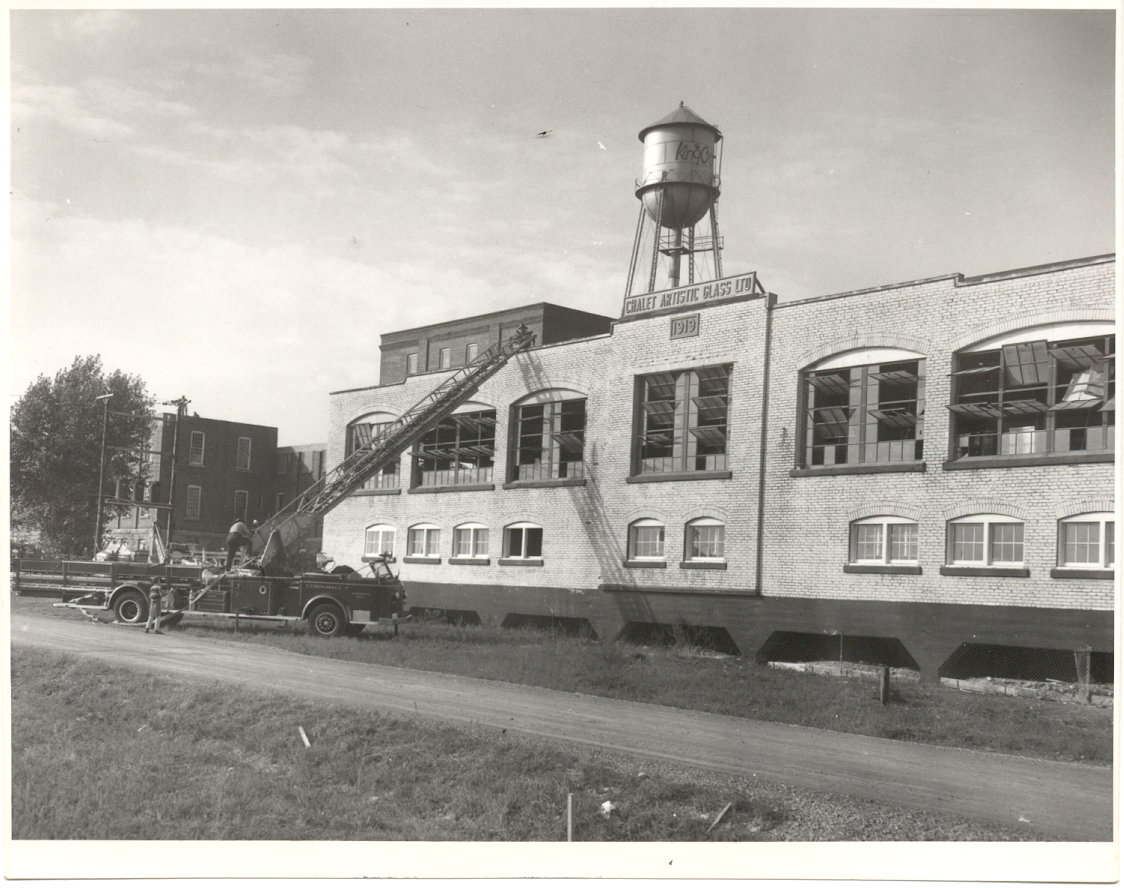

Photo courtesy of Paolo De Marchi. Son of Chalet artist Roberto De Marchi and member of ‘50 Shades.’

Circa 1962. The Chalet Artistic Glass factory, 50 Harbour Road, Cornwall Ontario, occupied the 1919 addition to the Dundas Mill. Chalet operated here, from 1961 (before name change from Murano Glass to Chalet Artistic Glass in 1962) until its closure in 1975. Photograph from the Cornwall Community Museum archives.

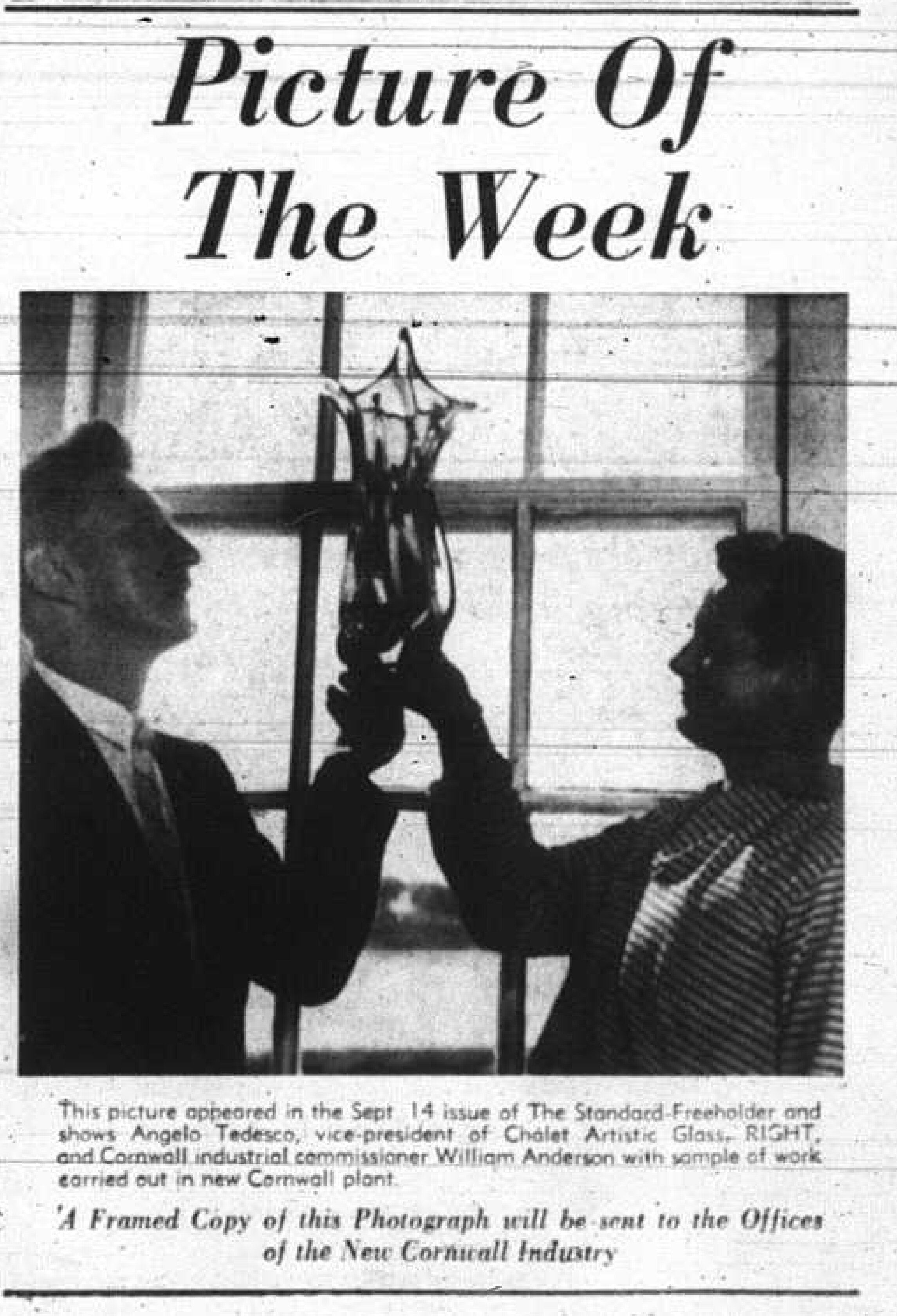

At left, Cornwall’s Commissioner of Development, William Anderson, with Chalet owner Angelo Tedesco (right). Admiring a “crystal twist” vase. The Standard Freeholder, September 21, 1962. Photograph from the Cornwall Community Museum archives.

After 16 months of operation, Murano Glass suffered a fire which decimated its Quebec factory. Therefore, the timing could not have better for the company to rebuild in Ontario. Murano Glass was one of 18 businesses that took advantage of these incentives to relocate to Cornwall. With much fanfare, Chalet Artistic Glass officially began production the morning of September 14, 1962. Some things had not changed - the budget was still limited. They hired no new glass blowers and there was only one furnace. Early pieces were in traditional Venetian style – elaborate and ornate. Its future was not secure. However, other huge changes were about to take place. Sid Heyes from Toronto had joined the company as President, and Garry Daigle, from Montreal, had become Sales Manager. This was a pivotal point for Murano Glass as Daigle and Heyes were insistent that Canadians would be attracted to glass of a more modern design. They persuaded the three owners to adopt this vision and, consequently, a new company path became decided and significantly this included a name change for the company. It now was Chalet Artistic Glass. With the name change, design,, branding and production all shifted as well. The glass blowers were increasingly inspired to generate art glass and lead crystal pieces with smooth, fluid lines, dramatic shapes and vibrant, striking colours. These pieces were created by techniques rooted in Venetian tradition but evolved into free-form hand worked “stretch” translations of the art form. In the words of Angelo Tedesco, “We had to change Venetian design to a small, modern design. Less artistic but more useful. Artistic for Canadian homes.” From “Why Canada,” 1965.

When sales hit $200,000, former Murano Glass workers Carlo Fuggia and Mirco DeValentina, rejoined the new company in Cornwall. Sabatino DeRosa, the third Murano glass employee, stayed in Montreal and worked briefly at EDAG before joining Lorraine Glass Industries where he would remain until its closure. Orders continued to increase, and to convey a clear statement to consumers that this was a Canadian company producing handmade Canadian designs for Canadian tastes by skilled artisans, the company changed its name to Chalet Artistic Glass. This second name change, which occurred in late 1962, also completed the vision initiated by Daigle and Heyes although the owners selected the name with Angelo Tedesco insisting upon “Chalet” as he felt it “Sounded Canadian.”

As sales grew, Angelo Tedesco – the Chalet Vice President and General Manager as well as one of the owners - realized the company needed more master glass blowers. He persuaded eight skilled glass blowers who arrived from Murano in 1962 to work at Lorraine Glass Industries to, instead, work at Chalet. The team expanded again in 1963 when Antonio Tedesco, a specialist in grinding and polishing glass, also joined his brothers. Many other family members found positions with the company, working in the sales and administrative offices, the factory showroom, and in various factory departments. Angelo is credited with having played an invaluable and instrumental role in encouraging more Murano glass blowers from Italy to join their peers at Chalet. From 1964 until 1974, a few more artists joined the existing team and other workers were hired from Cornwall and the nearby St. Regis Mohawk Reserve at Akwesasne to assist the masters. By 1972, seven furnaces were in production and nearly 70 people worked at the Chalet Artistic Glass factory.

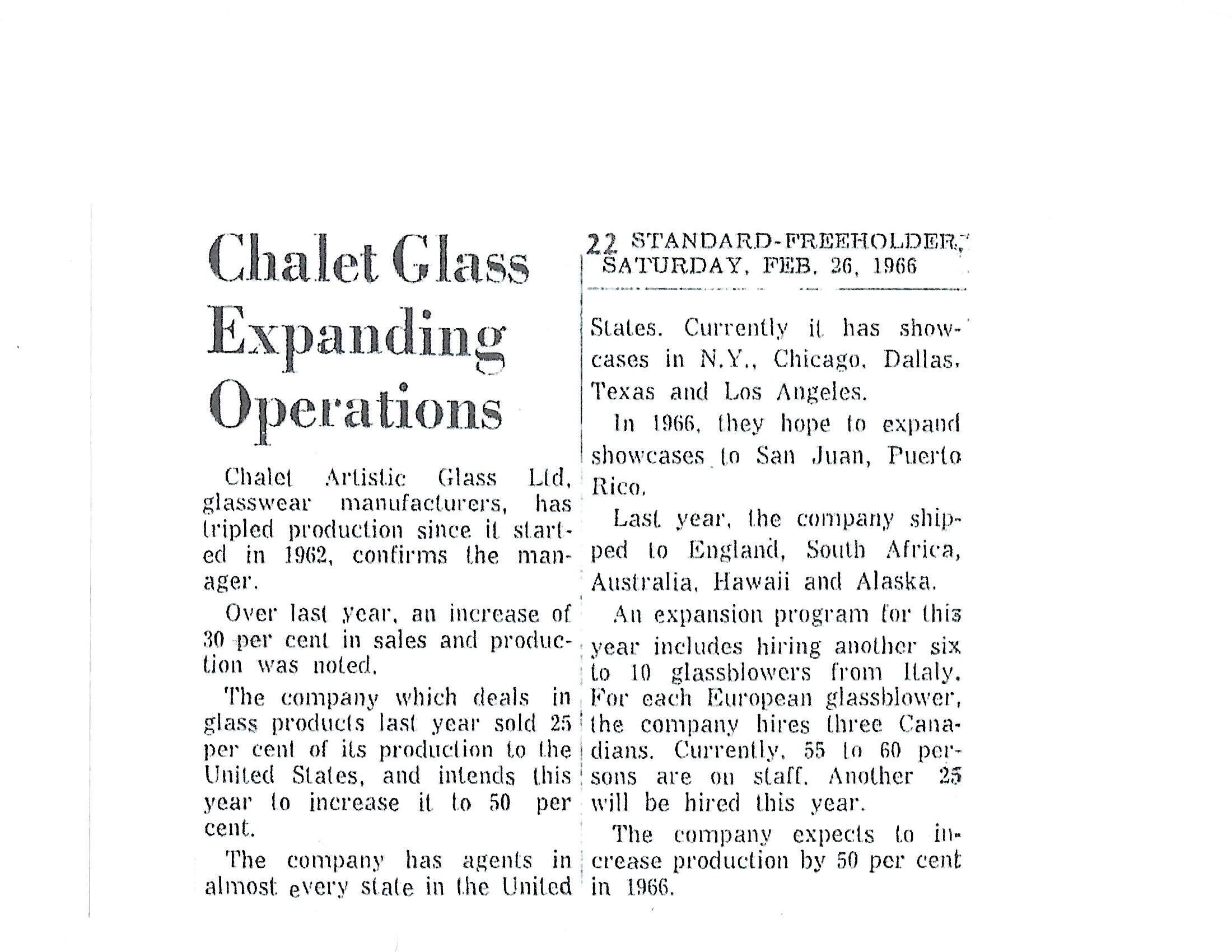

Cornwall Standard-Freeholder, Saturday, February 26, 1966.

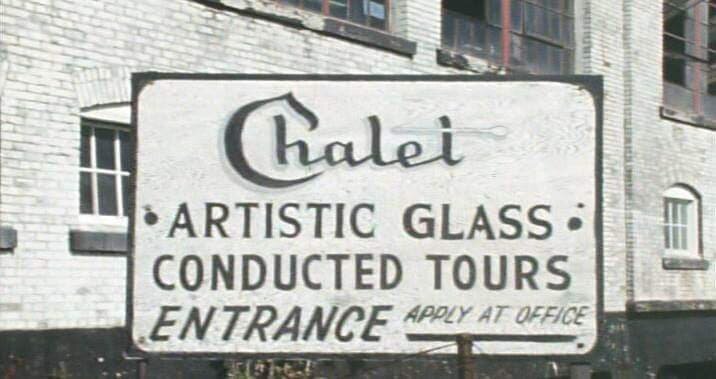

Maestro Giulio Gatto, Maestro Bruno Panizzon and Gianfranco Guarnieri remembered that from 1962 through 1965, despite having left Lorraine Glass Industries (Montreal) for Chalet, they only worked about six months each year. However, it was after 1965 that the increase in demand for ‘Chalet glass’ necessitated the artists work “7 days a week – every week.” Local school trips to the factory became commonplace; neighbourhood children considered it an adventure to sneak under the reject chute and claim small pieces of the discarded glass as personal treasures. Factory tours of the Chalet Artistic Glass factory, offered up to six times daily, became a primary tourist attraction in Cornwall.

Popular local attraction – for out of town tourists and Cornwall school children alike. Photograph from the Cornwall Community Museum archives.

1964. From the onset the company received considerable support from influential politicians and members of the community From left to right: the Honourable Lionel Chevier, Dr. G. W. Bowen, Cornwall Mayor Nick Kaneb and Madame Chevier. Photograph from the Cornwall Community Museum archives.

Chalet’s success was important to both the federal government and the Government of Ontario. They supported the company at home and abroad. In 1965, the Canadian federal government recognized Chalet’s unique position and contribution through a feature in a National Film Board of Canada documentary. The film, “Why Canada?”, stressed Canada’s cultural diversity and small business opportunity for new immigrants. In the film, Angelo Tedesco was interviewed and Sergio Pagnin was filmed creating an animal figurine. Other artists were photographed working on the factory floor. This film clip may be found in the ‘50 Shades Resource Library’ courtesy of Mario Panizzon. In 1966, the Government of Ontario featured the company in “A Place to Stand” filmed for the 1967 World Expo’ in Montreal. In 1972, the National Film Board of Canada featured the company and several of its artists once more in “Here is Canada” which again highlighted Canada’s cultural mosaic. Again, photographs from these are presented here and these film clips too may be found in the ‘50 Shades Resource Library.’ See link to the 50 Shades of Chalet found here in the ‘Group” pages.

Maestro Luigi Tedesco demonstrates his technique. Photograph from ‘Chalet’ by Mario Panizzon.

Chalet’s success was important to both the federal government and the Government of Ontario. They supported the company at home and abroad. In 1965, the Canadian federal government recognized Chalet’s unique position and contribution through a feature in a National Film Board of Canada documentary. The film, “Why Canada?”, stressed Canada’s cultural diversity and small business opportunity for new immigrants. In the film, Angelo Tedesco was interviewed and Sergio Pagnin was filmed creating an animal figurine. Other artists were photographed working on the factory floor. Many may be seen here and this film clip may be found in the ‘50 Shades Resource Library’ courtesy of Mario Panizzon. In 1966, the Government of Ontario featured the company in “A Place to Stand” filmed for the 1967 World Expo’ in Montreal. In 1972, the National Film Board of Canada featured the company and several of its artists once more in “Here is Canada” which again highlighted Canada’s cultural mosaic. Again, photographs from these are presented here and these film clips too may be found in the ‘50 Shades Resource Library.’

In 1967, Chalet Artistic Glass was given worldwide exposure at the Expo ’67 World’s Fair where pieces were showcased in the official Canadian Habitat Pavillon. The Honourable Lionel Chevrier, a former Member of Parliament representing Cornwall, High Commissioner to London, and now Head of Protocol for the world’s fair, was instrumental in a special-commissioned “maple leaf” production line from Chalet. The smaller versions of these centerpieces were available for purchase and the largest were given to dignitaries as gifts. On trips abroad, Cabinet Ministers and trade delegates took Chalet pieces as gifts for their foreign counterparts and Canadian embassies proudly showcased Chalet product. Politicians had a vested interest in Chalet’s success as so much federal money had been invested in Cornwall revitalization projects.

Larger centerpiece (middle) is flanked by two of the smaller.

It is believed that the Province of Ontario also called on Chalet’s talents to produce this specially designed paperweight piece to gift to trade delegates from Quebec.

The passage of time did not diminish official accolades as, on April 29, 1999, Canada Post issued a series of 8 commemorative stamps to honour the “Traditional Trades.” The 3-cent stamp in this series payed tribute to the art of glass blowing and the artists who make their glass speak to us.

As Chalet Artistic Glass had been singled out repeatedly in the past by the Canadian government as a symbol of excellence, cultural diversity and innovation, it is more than likely that they were a major inspiration for this recognition.

It is thought this paperweight was one of a dozen that the Province of Ontario commissioned from Chalet in honour of a trade delegation from Quebec. The inclusion is that of the blue flag iris, which is the flower native to Quebec that most closely resembles the fleur-de-lis. In 1999, after years of delays, the Quebec government finally gave into public and botanical pressure and, replacing the Madonna Lily, made the iris Quebec's provincial emblem. Photograph courtesy of Kevin Hall, member of ‘50 Shades.’

Most recently, in 2017 and 2019, the Canadian government again placed Chalet pieces in embassies and their residences throughout the world.

Colours gleamed. Lines flowed. Shapes were dramatic. The unique blend of talent, skill, experience, and personality of the Chalet artisans allowed these artists to produce fabulous, imaginative pieces of glass. They are recognized as the originators of Canadian free-form artistic glass. Their products were novel, beautiful, and affordable: ranging from $7 ashtrays to $180 vases. Chalet offered more than 100 varying styles of lead crystal and 400 items of glassware. The company’s range included: tableware, centrepieces, bowls, vases, book ends, candleholders, baskets, lamps, pitchers, wine glasses, water goblets, wine bottles, decanters, paperweights, ashtrays, cigar bowls, decorative birds, Madonna figurines, Christmas trees, animal figurines, sailboats, fruit, bombonniere, and mushrooms. Inventory did not remain stagnant. 1970 saw the introduction of new lines such as the ‘Canadiana Cranberry’, the ‘End of Day’, ‘Canadian Heritage Glass’ and the ‘Opal with Gold Flecking.’ Two years later the crystal and cranberry in crystal lines were added. Distribution in Canada was done through N.C, Cameron and Sons Ltd., and in the United States through Riekes Crisa. These were the last new full lines that Chalet introduced.

Although the Cornwall factory location had a showroom, the main sales office was in Montreal. Pieces available through either of these locations could be etched with the company logo, marked with a foil sticker, or given hang tags. Specific lines produced for retailers and distributors were usually marked with their own stickers. Many independent boutiques often added their own stickers or markings to both marked and unmarked Chalet pieces. Also commonly used were generic “Made in Canada” stickers and other labels proclaiming the quality of the glass.

Initially Chalet Glass had had only one sales distributor: Tex Novelty (Roy Craft) in Montreal. In early 1963, Eaton’s became the first of Chalet’s national chain store retailers. 1963 also saw the addition of national distribution through Simpsons, and Morgan’s (The Bay) department stores. By 1966, Chalet had overseas distribution as well: London, England and Johannesburg, South Africa. This was the first time that Canadian glass had ever been exported to England. However, foreign distribution was not without its challenges; the London sales office lasted for only two years and the initial South African link collapsed after one year. Despite this, another representative in Durban was successful from 1969 until 1973. The early 70s was a period of forging connections with Chalet and Birks beginning their partnership in 1970 and Chalet - through a press release - proudly announcing the additions of American distributors Riekes Crisa and N.C. Cameron and Sons in Toronto in March 1972. The press release proclaimed that Chalet art glass was now in widespread distribution across North America. Meanwhile, in the United States, distribution also flowed from Chicago, Omaha, Los Angeles, New York and Dallas though by 1974, Riekes Crisa directed Chalet’s presence in the American market solely from Omaha, Nebraska.

In the 1970s, heavy crystal and leaded glass became increasingly expensive to make. Distributors were constantly making demands: they wanted more expensive product – crystal - and at reduced costs. This was compounded by the 1970s energy crisis and the ensuing inflation spike which caused an insurmountable increase in costs across many industries. Simultaneously, tastes were also changing and the heavy leaded crystal hand blown stretch pieces were no longer in wide demand. Chalet struggled to find lines that could replace these pieces and achieve the same popularity. They reduced production of the heavy crystal and began heavily promoting Canadiana Cranberry. The company also looked to the ribbed CH lines, the End of Day and opal glass and the Riekes lines of crystal and cranberry glass as answers to the shifting trend. The company’s increased production of the moulded pieces dismayed the artists. They did not feel they were art but pieces produced solely to address Chalet’s increasing need to reduce costs as sales floundered. Other glass makers were not immune to the changing circumstances – Lorraine Glass Industries closed in 1974.

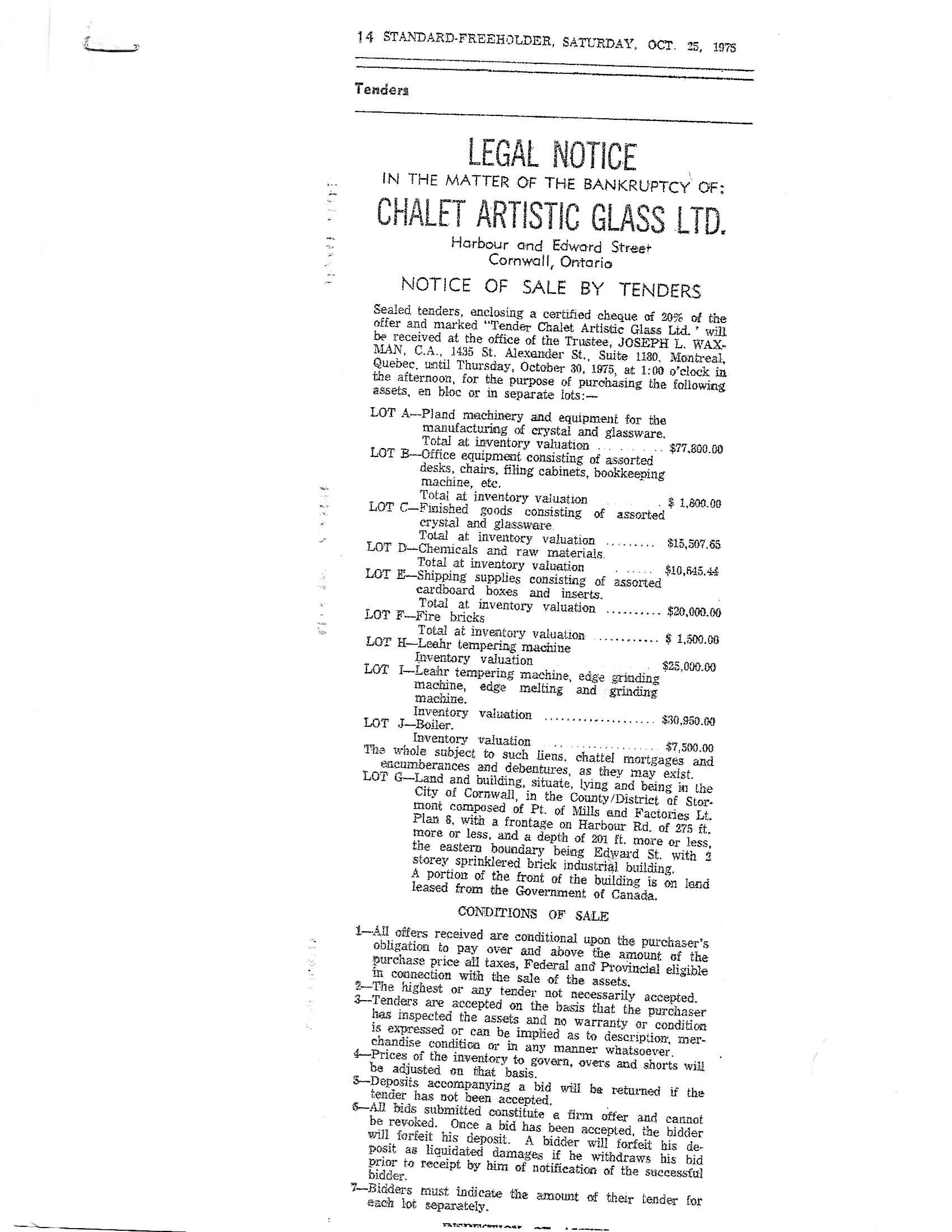

In 1974, Sergio Pagnin replaced Sid Heyes as President, and Angelo and Luigi Tedesco became Vice Presidents. Garry Diagle remained as Sales Manager. However, reorganization and a temporary three-month closure did not solve the company’s problems and in June 1975, the company filed for bankruptcy. Attempts by a group of employees, known as the “Group of 8”, to stop the bankruptcy proceedings and to continue production as Chalet Artistic Glass failed. From the Cornwall Standard-Freeholder newspaper on Saturday, October 25, 1975 – the “Legal Notice in the Matter of the Bankruptcy of Chalet Artistic Glass Ltd.” from the Montreal law firm of Waxman, Levine, Eidelman & Co. requesting tenders for the purchase of assets and conditions of sale. Here is the listing of assets for sale:

Of particular interest, see “Lot C” – the evaluation of “crystal and glassware” inventory.

The company assets were sold on October 30th, 1975 leaving some 36 artisans and talented tradesmen forced to leave Cornwall or to remain and seek unfamiliar jobs in a time rife with economic uncertainty, escalating inflation, and rising unemployment. Another 30 employees, administrative and sales support, also lost their jobs. The equipment and finished inventory, but not the building or name, were bought at auction by Angelo Rossi (see the section with Chalet artists’ biographies) in partnership with entrepreneur Morris Jaslow. Please refer to the article “Chalet/Rossi Connections and Confusions.”

Some of the Murano immigrants and their families stayed in the Cornwall area while others returned to Italy. Angelo Tedesco was among those who stayed, remaining in Cornwall where he worked etching and cutting glass. Among those that left were Luigi Tedesco, Franceso and Sergio Pagnin. Upon their return to Murano, they formed a small company, Pagnin & C., which specialized in Venetian lighting fixtures. Today Christopher Pagnin carries the family tradition into the third generation; still in Murano, with Pagnin Glass. In 1979, Angelo Tedesco and a partner, Jean Denis Legault, opened a very small glass house in Saint Zotique, Quebec. ‘Christallerie Chalet Vie et Art’ was very short lived – 2 years and had only 2 small ovens. Most significantly, Chalet Maestro Giulio Gatto and Chalet artists Roberto De Marchi, Giovanni Voltalina and Paul and Marcel Gravelle worked there.

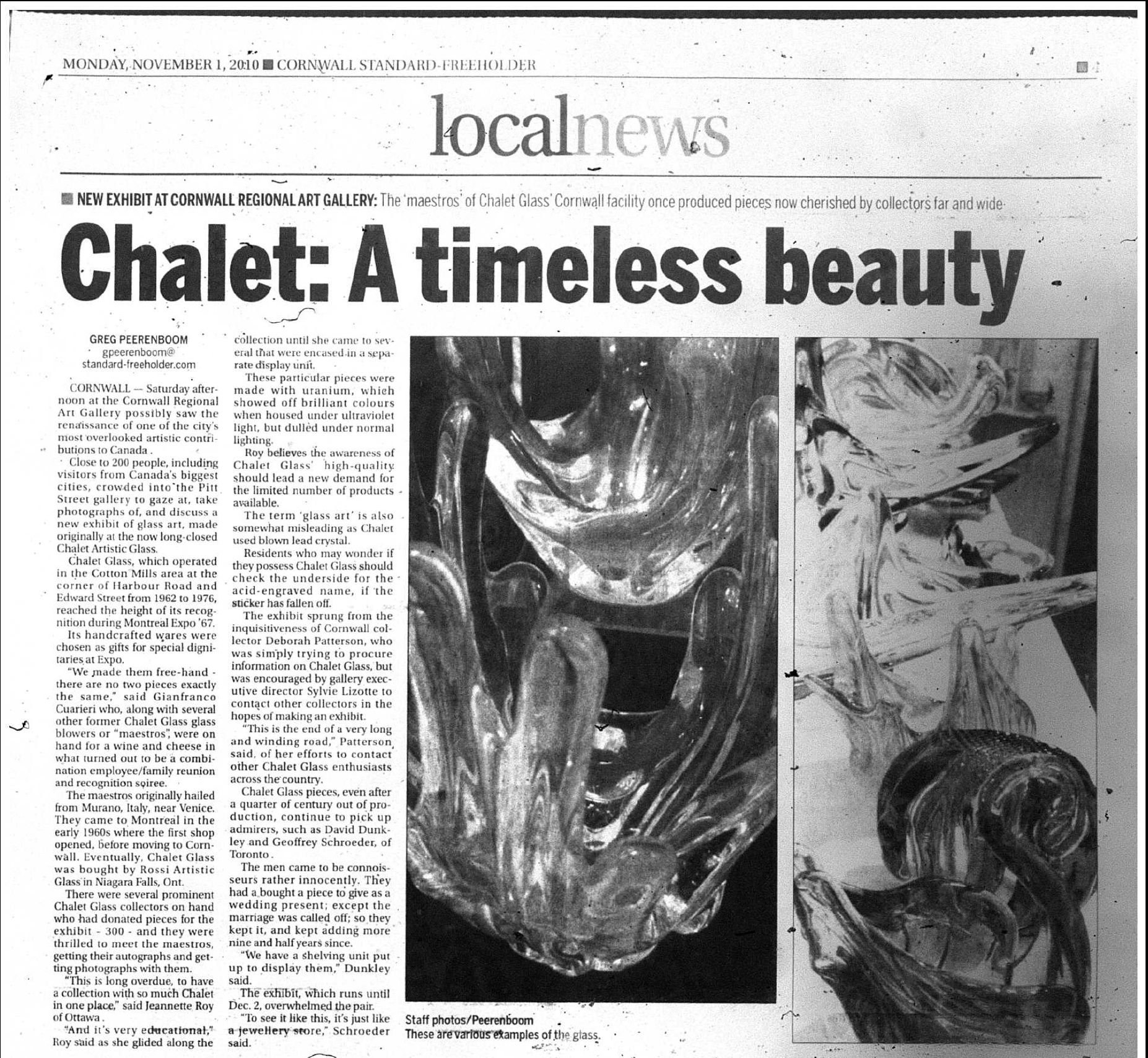

Although the 1919 brick mill building at Harbour Road and Edward Street in Cornwall that housed Chalet was lost to a fire, the soul of their creativity endures. In Eastern Ontario, across the country, and around the world, there are ardent collectors of Chalet Artistic Glass. We were able to thank the artists and their families for their legacy on Tuesday, October 26, 2010 when a 6-week long exhibit, “The Art & Artisans of Chalet Glass,” opened at the Cornwall Regional Art Gallery. Colours gleamed afresh, lines flowed anew, and dramatic shapes awed once again.

The unique blend of talent, skill, experience and personality of the Chalet artists and their fabulous, imaginative pieces of glass received long overdue tribute.

Over 200 people attended the Saturday, October 30, 2010 opening reception of “The Art & Artisans of Chalet Glass” exhibit, Cornwall, Ontario. It was described by the Cornwall Standard-Freeholder as, “… part family/employee reunion and part recognition soiree.”

Chalet artists attending the exhibit’s opening reception. Facing the camera, (left to right) Giovanni Voltalina, Antonio Tedesco, Gianfranco Guarnieri, Roberto De Marchi and Maestro Bruno Panizzon. Maestro Giulio Gatto and Gian Paolo Bastianello were unable to attend but toured the exhibit later with me.

Andrew Patterson and Claudette Blue, foreground, Mario Panizzon left back ground and Chalet artist Gianfranco Guarniere center background.

Bruna and Irma Tedesco (foreground) attend the opening reception of the “The Art & Artisans of Chalet Glass.” Also, in background, Ed Lumley, former Cornwall Mayor, with his wife. Cornwall, Ontario. Saturday, October 30, 2010.

On display, both the 14” (blue) and the 12” (orange) 1967 “Expo” leaves. Rare.

The Chalet animal figurines are perennial favorites. The assortment on display at the exhibit.

Chalet Maestro Bruno Panizzon (wearing Chalet name tag) explains some Chalet finer points to Deborah Patterson and Mario Panizzon (back to camera) at opening of “The Art & Artisans of Chalet Glass” exhibit, Cornwall, Ontario.

Excited collectors, proud family members and the guests of honour – Chalet glass and the artists who made it. Artists in this photograph (from left to right) Giovanni Voltalina, Maestro Bruno Panizzon, Roberto DiMarchi and Gianfranco Guarnieri with back to camera. Also shown are reception attendees including Mario Panizzon (between Maestro Bruno Panizzon and Roberto DiMarchi).

Paolo De Marchi, wearing poppy pin, at the opening reception.